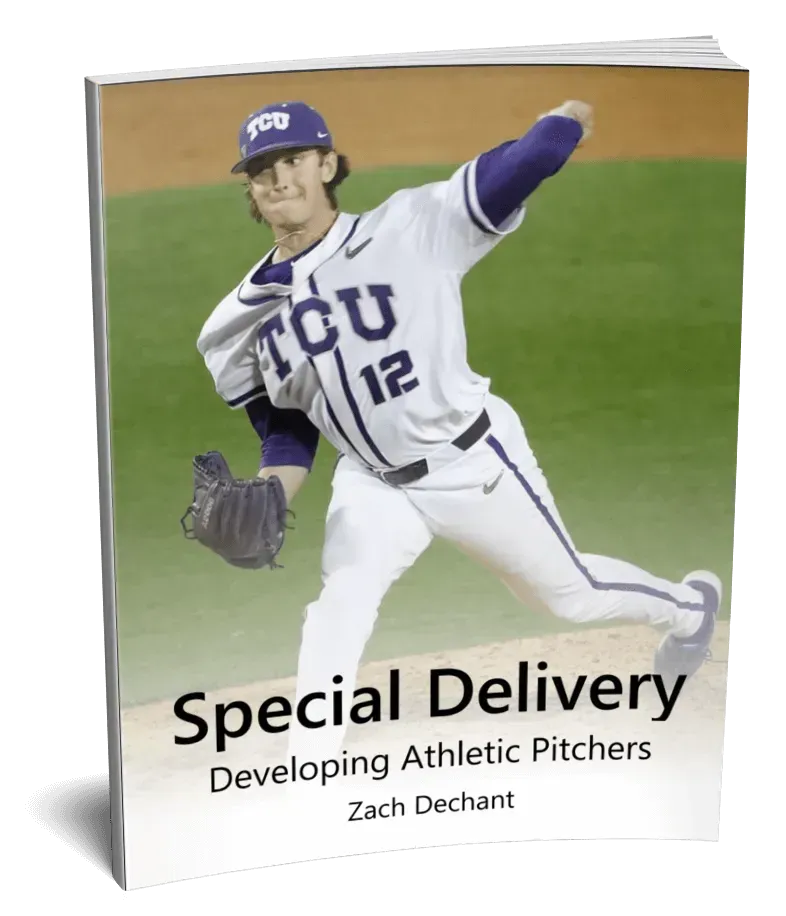

Free Pitcher's Training eBook Reveals

How To Develop Athletic Pitchers And Train Them With An

Emphasis On Speed, Power & Movement

...and they must be treated as such. The act of pitching is an explosive, total-body movement.

There is nothing slow about it. Thus, our

overarching goal in training pitchers is to make

them fast, powerful, and explosive -- so that's how

they should train.

However, several factors separate pitchers from the rest of the team and these should be taken into account when developing a training program.

In this PDF eBook, you're getting the complete, individualized strength & conditioning approach utilized to assess, develop and train athletic pitchers that move explosively.

Movement Over Maxes

Developing The Foundation for Baseball Performance

"If you want to improve your program and give your athletes a winning edge, this book is a must!"

Movement Over Maxes is a Foundational Program that serves as the starting point for any athlete. It functions as a guide for all coaches to begin to understand and implement basic movement patterns with a long-term development approach.

This was created for the coach who wears every hat for their program... The coach who mows the grass, drags the infield, handles the equipment, AND trains the athletes! This is for the coach who devotes their life to not only creating better baseball players, but growing boys into men through the sport.

Misconceptions of Speed Development - TFC Podcast Episode 3

Misconceptions of Speed Development - TFC Podcast Episode 3 ...more

blog

February 25, 2022•0 min read

Tracking Tonnage: Waste of My Time

Tracking Tonnage: Waste of My Time ...more

blog

February 14, 2022•3 min read

Top 10 Takeaways From my Internship Experience at TCU

Top 10 Takeaways From my Internship Experience at TCU ...more

blog

November 14, 2021•11 min read

CONNECT WITH ZACH ON TWITTER

ABOUT ZACH DECHANT

Zach has been in place since 2008 at TCU and is the current Assistant Athletic Director of Human Performance. He oversees the development of Baseball. Alongside those priorities he also handles the development and implementation of the TCU Sports Performance Internship Program that has been in place for over 15 years. Over that time the internship program has encompassed 40+ semesters and 250+ intern coaches that have moved on to all levels of professional, collegiate, high school, and private strength and conditioning.

During baseball off-seasons, Coach Dechant trains a group of 30+ current MLB / MiLB Frogs. The pro Frogs spend 4 months back on campus training for the upcoming season...

©️ 2024